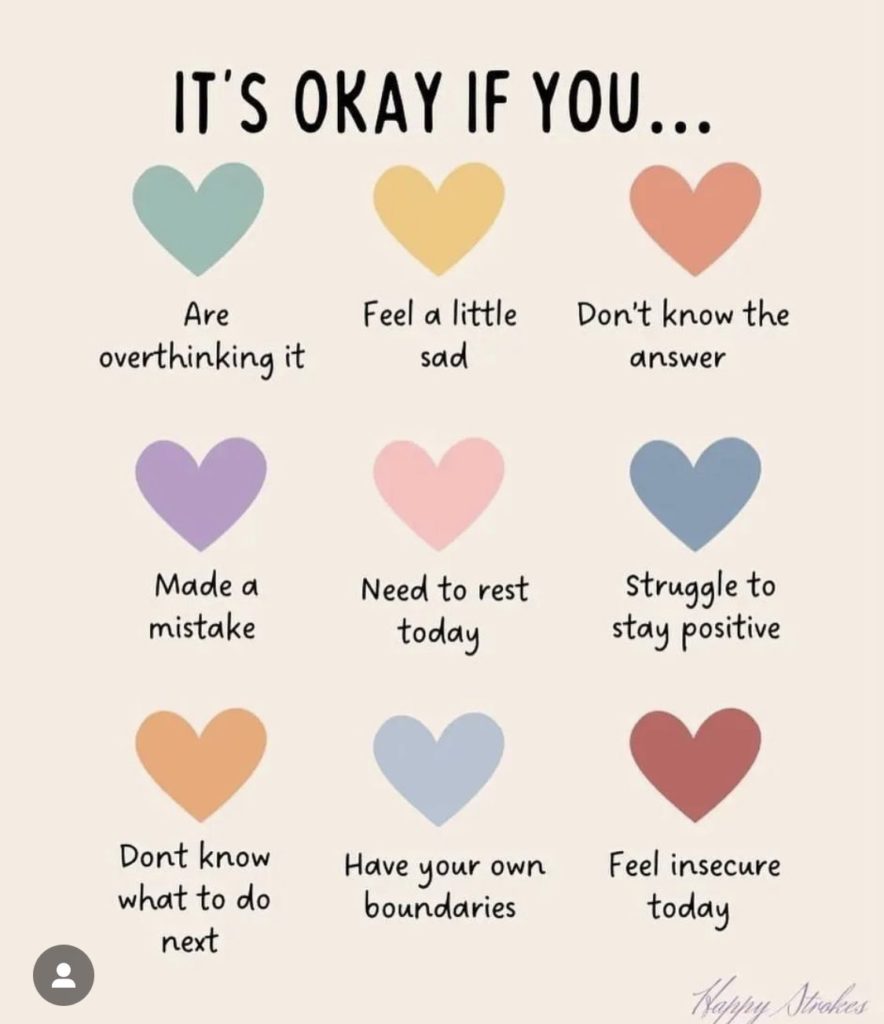

I want to start this blog by sharing a graphic from a social media post from a wonderful friend and colleague, Nicola Payne:

The graphic Nicky shared got me thinking about myself and my friends and family, but also about my work in dementia care and support.

I’m fine… but I’m really not

As Nicky says, it’s often easier for all of us to say, “I’m fine” than to really explain how we feel. I do this A LOT even though I could explain in much greater detail. How must a person with cognitive impairment, who potentially has to search for every word that they want to say, be feeling? Moreover, how do those of us supporting a person with dementia build into our support a true exploration of how a person is feeling?

Most people, even without training or experience of dementia, might accept that a person doesn’t know an answer to a question or needs to rest but:

How do we support a person with insecurity? Do we just dismiss it with comments like, “You’re ok,” or “It’ll all be alright, don’t worry”? I looked at this in my November 2022 D4Dementia blog, detailing how reassurance is about more than just empty words or gestures.

How do we support a person who doesn’t know what to do next? Do we say: “Just sit here and have a nice cup of tea”? How are we finding out what the person might REALLY want to do? I’d suggest starting with life story work if you’re a professional who doesn’t know the person as well as you could.

But perhaps most notably of all:

How do we know, understand and support a person’s boundaries?

Do we even consider if a person has their own boundaries? Things they just don’t like? Places on their body they don’t want to be touched? Ways in which they don’t want things done?

To understand boundaries, we need to know the person REALLY well. We need to respect what we know of their preferences and try to find out what they want in every interaction. Crucially, we need to appreciate that something we may personally be happy with someone else won’t be, and that’s not about that person being difficult or wanting to make life harder for those supporting them.

Where boundaries aren’t understood or supported, a person with dementia may only be able to express how they feel and what they want through what might be seen as ‘challenging behaviour’ – but that expression is entirely driven by our lack of understanding and respect for that person’s boundaries, not them being ‘challenging’.

Boundaries and personal care

Boundaries may exist in all of the elements of a person’s day, but they are most likely in personal care interactions. I’ve lost count of the times professionals have detailed how a person they are supporting is ‘resistant’ to aspects of personal care. In reality this often means that the person doesn’t feel comfortable about invasion into their personal space, or because personal care as it currently exists is involving touching a person in places they don’t want to be touched.

Reframing ‘resistance’ as ‘boundaries’ is an important change in narrative. Resistance makes the person sound like they are being awkward and should be complying (taking us back to the point about ‘challenging behaviour’). Boundaries are about the person being in-control, having the autonomy to say what they do and don’t want for themselves and for that to be respected.

The difficulty for professionals is that they are often only trying to keep a person clean, dry and comfortable, and so feel compelled to try and work through the person’s ‘resistance’ in order to complete their ‘task’. My advice in these situations would always be to support the person to take the lead. Promote as much autonomy and independence as possible, accepting that there are certain things that the person may only want to do themselves. Yes, that may mean these things aren’t done as thoroughly as a professional might, but how would you feel if someone was coming at you with wet wipes to clean your bottom and you didn’t want them to do it?

With time and trust and the right relationship with the person, there may be staff members who can work with the person so that when the person has done what they need and want to do for themselves, they can be supported by their trusted professional to discreetly check and make sure their bottom is completely clean and dry.

Know a person’s back story

Boundaries won’t just exist around the most private areas of our bodies. One of my personal boundaries is around my face, and there is a back story to why that is. When my daughter was a toddler she launched herself onto a bed I was lying on and scratched by cornea. This was diagnosed as a corneal abrasion, which became a recurring corneal abrasion, meaning it will never heal and is frequently painful. For me, someone coming at my face with a wash cloth would result in me saying “no” and not wanting that interaction to go any further, and if the intrusion continued I would try to stop the person. What is that if not what some people might call ‘challenging behaviour’?

The learning here is that there is often a back story to a person’s boundaries. So again, life story work, reflecting after each interaction and working in a person and relationship centred way are crucial. For some people their back story may be highly personal, intimate and distressing – I’ve had a few instances of this in my work in the last few years – and if you don’t keep an open mind and consider all possibilities, clues can be missed that will lead to care and support being given that causes immense distress to a person.

So always be that enquiring individual, the person considering the nine hearts on Nicky’s graphic and asking questions of the way a person with or without dementia is feeling, so that you (and your team if you have one) can provide the best possible support.

Until next time…

You can follow me on Twitter: @bethyb1886

Like D4Dementia on Facebook